Introducción

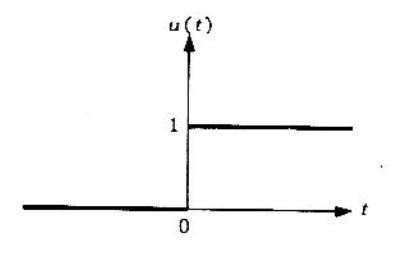

La función escalón unitario está definido como

Después, se va a suponer que

Se recuerda que , se observa también que

Donde está definido por

Por lo que

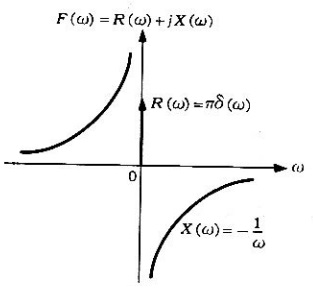

excpeto cuando . Por la linealidad de la transformada de Fourier

Ahora, se agrega una nueva suposición

donde es una función ordinaria y

es una constante.

Se recuerda que , por lo que

de donde se concluye que , y

es una función impar.

Para encontrar , se determina de la siguiente manera

Como

Regresando

Figura 1. Función escalón unitario.

Figura 2. Transformada de Fourier de la función escalón unitario.

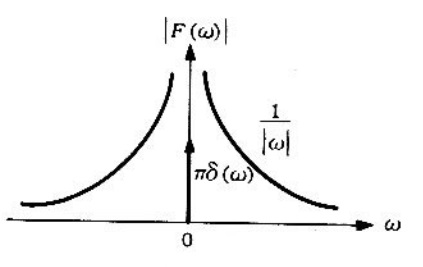

Figura 3. Espectro de la función escalón unitario.

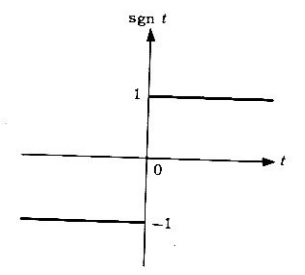

La función signum

Sea y

. La función

se llama signum y está definido como

Como la función es una función impar de la figura 4,

será imaginaria pura, en consecuencia, es una función impar de

.

Ahora, se sabe que

Continuando

Donde es una constante arbitraria. Como

debe ser imaginaria pura impar,

. De donde

Figura 4. Función sgn t

Figura 5. Espectro de la función sgn t

Teorema

Teorema 1. Como , se observa que

debido a que .

Entonces, si , por lo tanto